The Black Rhinoceros - Diceros bicornis

by Yasmin Markides

The purpose of this wildlife management plan is to gather the necessary information on how to introduce a Black Rhinoceros to an area. The aim is to provide a detailed report on the steps to take when introducing a Black Rhino to and area. In this management plan there will be various categories covered. The description, distribution, habitat and behavior of the species will be discussed.

The food, water, fencing and security requirements for the species will be specified. The economic value will also be discussed to determine the usefulness of the Rhino on a ranch. Other topics that will be discussed are the; potential impact the species will have on the habitat, the impact the species will have on other wildlife as well as the capture and translocation of the species and the counting. The Rhino has a very large positive impact on the environment, therefore it needs to be conserved and well managed in order to save the species from extinction.

Description

The Black Rhinoceros is the smaller of the two species. It has a hooked upper lip, this is the main way to distinguish between the two species as the White Rhinoceros has a square upper lip. This hooked upper lip helps the Black Rhinoceros get leaves off of trees when they are browsing (Harvey, 2017). The Black Rhinoceros has two horns, although occasionally it may grow a third posterior horn. The Black Rhinoceros is usually 130-180cm in height and weighs 1700-2300 kilograms (Harvey, 2017).

Distribution

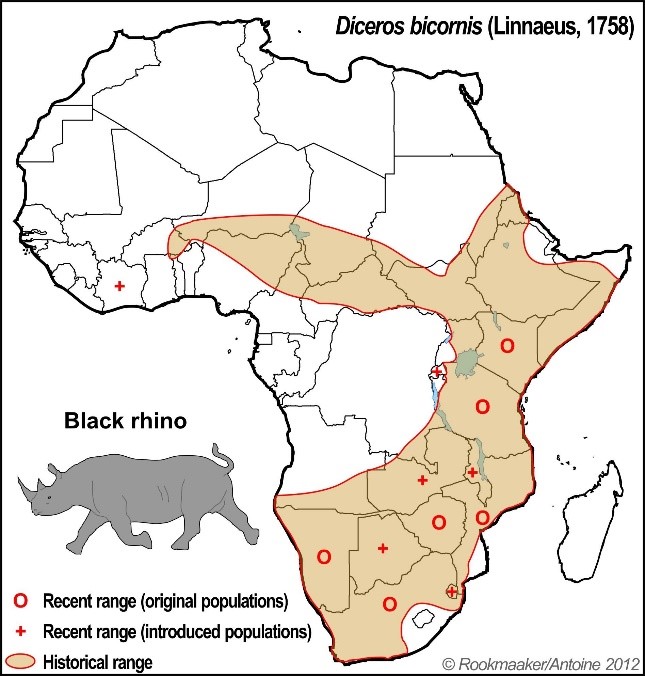

The Black Rhino originally occurred throughout Africa ranging from South Africa all the way up to Burkina Faso (Figure 1) (Harvey, 2017). Some countries included in this historical range are; Botswana, Zambia, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Nigeria and Chad (Figure 1) (Harvey, 2017). Original populations of the species now occur in; South Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Tanzania and Kenya (Figure 1) (Harvey, 2017). Recently introduced populations occur in; Botswana, Swaziland, Malawi, Zambia, Rwanda, and the Ivory Coast (Figure 1) (Harvey, 2017).

Figure 1: Black Rhino Distribution Map (Harvey, 2017)

Habitat

Habitat preference

The Black Rhinoceros occurs in deserts, grasslands, semi-arid savannah, woodlands, forests, and wetlands (Harvey, 2017). Black Rhinos are browsers and enjoy eating from small Acacias that are not hidden by grass. They also enjoy other palatable woody species as well as palatable herbs and succulents for example; Euphorbiaceae. Therefore they prefer to be in bushveld habitats (RH & K, 2016).

Potential impact on habitat

Black Rhinos are browsers and usually browse in large open areas that are not covered by grass. They tend to occupy only certain areas for long periods of time (Lush, et al., 2015). Therefore the Black Rhinoceros could potentially cause sheet erosion in the areas it prefers to browse in.Requirements

Food

Black Rhinos gain most of their energy from the fermentation of fibrous plant material. They are strictly browsers and require habitats that contain small trees and shrubs with succulent leaves. If these plants species are not present on the land where the Black Rhino is being held, then pelleted compound feeds should be provided in feeding troughs in appropriate areas of the land (Clauss & Hatt, 2006).

Water

Black Rhinos are water dependent animals therefore they require water to be in close proximity to their preferred browsing sites. As in most dark skinned animals require mud and dust to protect them from the sun to avoid over-heating (Meyer, 2012). A number of natural waterholes are required throughout the habitat of the Black Rhino. As well as a number of mud pools for them to wallow in (Meyer, 2012).

Behavior

Black Rhinos males are solitary animals and rarely interact with others unless when mating. The most stable relationship in Black Rhino species is the relationship between a female and her most recent offspring (Hutchins & Kreger, 2006). Black Rhinos tend to defecate in large piles of dung, spray urine, break vegetation and scrape their back feet in dung piles to release odors, to make others aware of their presence. Black Rhinos have exclusive territories (Hutchins & Kreger, 2006).

The movement of Black Rhinos is influenced by temperatures and the distribution of food and water. They tend to spend the warmer times of the day wallowing in mud pools or in shade under trees. Their slow digestive systems forces them to spend most of their active time foraging (Hutchins & Kreger, 2006). Both male and females seek out mates, this makes them polygamous. With regards to predators they almost always have a flight response, sometimes running for long distances without stopping. The Black Rhino has a mutualistic relationship with Oxpeckers, these birds remove ticks and fleas from the skin of the Rhino and also give alarm signals when there are threats in close proximity (Hutchins & Kreger, 2006).

Management

Security

Precautions need to be taken in areas populated by Black Rhinos to avoid poaching. There are many strategies to ensure no poaching occurs, such as; having observation posts, sufficient communication and infrastructure (Watson & King, 2011). Observation post should be placed on high land to ensure visibility. These posts will be manned by gone or two guards that have shifts to ensure there is someone on the lookout at all times of the day and night (Watson & King, 2011).

Communication is important between lookout guards and operation offices. Good communication will ensure that there is quick response to threats (Watson & King, 2011). Good infrastructure is one of the most important aspects in security. It is necessary to have vehicles that are appropriate for the action towards anti-poaching. Surveillance equipment and radios are also important to ensure good communication. In some cases light aircrafts are useful for easy sightings of the location of poachers and Rhinos that are in potential danger (Watson & King, 2011).

Fencing

Black Rhino require a Class 4 fence, this is the special class of 1.8m and has various degrees of electrification. The fence must be Bonnox or a 15 properly spaced wire strand stock-proof fence (Brown, et al., 2014). A minimum of 2 equally spread electrical strands with a minimum current of 6000V and must be mounted on an off-set bracket on the inside of the fence at 500mm and 1000mm. No cables are required (Brown, et al., 2014).

Capture and Translocation

When it comes to the capturing and translocation of the Black Rhino planning is essential. The right time of the year needs to be considered as this can influence the well-being of the Rhino and also the movement of vehicles. Therefore it has been found that the best time of the year to capture and translocate if during the dry months of the year (Morkel & Kennedy-Benson, 2000, pp. 4-6).

Chemical immobilization is the best method used to sedate the animals. Black Rhinos have been found to be good candidates for this method, if the Rhino is darted with the correct dosage, induction is fairly fast and predictable, and vital functions can be maintained with no issues (Morkel & Kennedy-Benson, 2000, p. 8). This method is fairly tricky as, the Black Rhino has very thick skin and can often run and hide between thick shrubs. Therefore chemical immobilizers should only be given to the Black Rhino by a person who has been trained to do so (Morkel & Kennedy-Benson, 2000, p. 8).

Monitoring of the Black Rhino is vitally important once it has been darted. A quick examination should be done to determine the age of the Rhino as, older Rhinos need special care (Morkel & Kennedy-Benson, 2000, p. 15).

Capturing and transport of the Black Rhino can be done numerous different ways once the Rhino has been sedated and checked. Vehicles such as trucks, need to be recently serviced and in good condition before transporting a Black rhino. Spare wheels and other tools need to be kept with the vehicle to ensure any mechanical problem will be fixed fast (Morkel & Kennedy-Benson, 2000, p. 22).

Airlifting can be done if the distance the Black Rhino needs to travel can be done with a light aircraft within the sedation period. Other more effective ways would be to transport the Rhino in a large crate that sits on a truck. With this method the Rhinos need to be kept calm as they often traumatize themselves and cause self-injury (Morkel & Kennedy-Benson, 2000, p. 23).

Once Black Rhinos have been translocated to a new area, it is best to keep them in a Boma for a minimum of one month to ensure they are habituated to their new surroundings. This will also ensure that no damage is done to the surrounding areas due to a stressed Rhino (Morkel & Kennedy-Benson, 2000, p. 22).

Counting of species

For the counting of Black Rhino there are two methods that are effective. One method is to fly over the area with a light aircraft and count the number of individuals that can be seen (Hofmeyr, 2017). Another method is stratified block counting. This method is more effective but can only be done if the appropriate technology is available. An area of land is divided in into 3x3 kilometer blocks, this is done with computer software (Hofmeyr, 2017). Each block is checked for high or low density of Rhinos by looking at the vegetation growth. Pilots in light aircrafts fly over the specific blocks and count how many Rhinos are visible in each block. A second check is done of each block to determine if no Rhino was missed and not counted (Hofmeyr, 2017).

Impact on other wildlife

Impact on other wildlife will only happen if there are other herbivores in the area such as; Elephant and Giraffe. Elephants and Giraffe are browsers, therefore there could be potential competition between the three species (Watson & King, 2011). Although this rarely happen due to the different sizes of the animals and how they browse the leaves on trees at different heights and different times of the day. Close monitoring should still take place to prevent possible conflict between the species (Watson & King, 2011).

Economic value of the species

Black Rhinos have value to humans dead or alive. Although in recent years dead rhinos have had more value due to their horns and other body parts being sold in illegal trade. Trophy hunting pays a bit contribution to the economic value for dead Rhinos. Rhino conservation will succeed greatly if the value for alive Rhinos is greater than dead ones.

Ecological importance

The black rhino is referred to as an umbrella species. An umbrella species can indirectly protect many other species (Caramanus, 2017). There are millions of species of conservation concern, it can prove difficult to conserve all of these species at once, and therefore it will be useful to use an umbrella species such as the Black Rhino to make conservation decisions. In summary, when you save a rhino, you save an ecosystem (Caramanus, 2017).

CONCLUSION

The purpose of this wildlife management plan was to gather the necessary information on how to introduce a Black Rhinoceros to an area. The aim was to provide a detailed report on the steps to take when introducing a Black Rhino to an area. It was found that the Black Rhino is a fairly easy animal to introduce to an area. The Black Rhino has a good impact on other wildlife and its environment. If the correct steps are taken when introducing the Black Rhino to the area, the Rhino become successfully habituated to the new area. The black rhino was referred to as an umbrella species. An umbrella species can indirectly protect many other species. Therefore, the Rhino needs to be conserved and well managed to ensure good economic value and avoid extinction.

REFERENCES

Brown, C., Gildenhuys, P. & Hignett, D., 2014. Cape Nature Fencing Policy, Western Cape: Cape Nature. Caramanus, J., 2017. Black Rhino Conservation Programme. [Online] Available at: https://www.wwfkenya.org/our_work/black_rhino_conservation_programme_/ [Accessed 14 April 2018].

Clauss, M. & Hatt, J.-M., 2006. The feeding of rhinoceros in captivity, Zurich: Division of Zoo Animals and Exotic Pets.

Harvey, M., 2017. Black Rhino. [Online] Available at: https://www.worldwildlife.org/species/black-rhino [Accessed 14 April 2018].

Hofmeyr, M., 2017. First Dedicated Black Rhino Count Finds 55 Animals. [Online] Available at: http://www.krugerpark.co.za/krugerpark-times-4-3-blackrhino-count-24134.html [Accessed 14 April 2018].

Hutchins, M. & Kreger, M. D., 2006. Rhinoceros behaviour: implications for captive, Maryland: The Zoological Society of London.

Lush, L., Mulama, M. & Jones, M., 2015. Predicting the habitat usage of African black rhinoceros, Scarborough: Centre for Environmental and Marine Sciences.

Meyer, A., 2012. Rhinos Habitat. [Online] Available at: https://www.rhinosinfo.com/habitat.html [Accessed 14 April 2018].

Morkel, P. & Kennedy-Benson, A., 2000. Translocating Black Rhino. 1st ed. Ngorongoro: Frankfurt Zoological Society.

RH, E. & K, A., 2016. Diceros bicornis – Black Rhinoceros, Lesotho; Swaziland : South African National Biodiversity Institute; Endangered Wildlife Trust.

Watson, M. & King, J., 2011. Management Plan for the, Isiolo: Sera Management Team.

.jpg)